Filmmaker and curator Mike Stubbs, current director of the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology, recounts being one of the first to step through the wormhole of digital video editing.

This account is linear. It will, however, almost certainly be read by you, the reader, in the multi-dimensional space of the internet. It is an appropriate venue, therefore, for me to recount the story of one of the key cultural moments of the latter half of the last century, the point at which we started to rewire our brains to inhabit such crosswise spaces: the advent of non-linear editing.

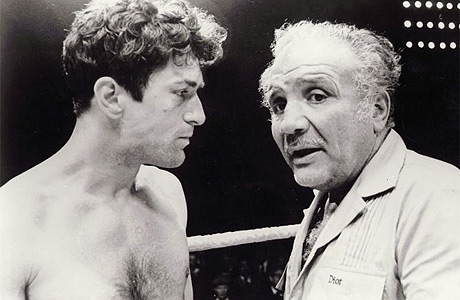

In 1991, one of Britain’s most important filmmakers, Michael Powell, gave a talk at Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff. Later, in the bar, we realised that his wife, who had accompanied him, was none other than the legendary film editor Thelma Schoonmaker. We asked her whether she might tell us more about her work; she agreed and, the following morning, I arrived armed with a VHS of Raging Bull. She talked us through how they recorded and dubbed smashing fruit sounds onto the images of boxing blows, the innovation of using the first 48-channel mix down and how the fight sequences benefited from changing the camera speed during shot.

Next to the room where we viewed Raging Bull was a cutting room, a more modest 16mm version of Thelma’s 35mm grown-up one, complete with film-bin (to hang up the individual shots), splicer (to chop up the film), pic-sync (sync sound and picture), chinagraph pencils (to label the shots) and a Steenbeck for viewing the sound and image together. This was the materiality of filmmaking made tangible by machines from the first industrial revolution. In another room, a U’matic video editing suite sat. I had spent hours in front of the contraption, watching and waiting for the video tape to spool through the giant cassette housings to get to the correct edit point, struggling to make slow motion and fast cuts.

In Dundee at the Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art I had access to a Quantel Harry, one of the first technologies for compositing, and a beloved Panasonic M2, a video editing deck with dynamic tracking, which enabled speed changes on the fly, just like those used in Raging Bull, but in post production. My short film Sweatlodge was edited there on the M2, an experimental documentary of performance group Man Act, filmed on Super 8, would speed up and slow down almost imperceptibly.

Non-linear editing arrived a couple of years later (a decade after the word processor, another transformatory technology of the same family) and, with its random access memory and ability to find data from a hard drive, led to the pioneering of many new editing techniques and applications. This was closely followed by similar advances in digital audio mixing and manipulation, for which we have to thank for the particular sonic stylings of, for instance, ZTT, the Art of Noise and Grace Jones.

To cut and paste, make multiple copies and store the shots and sequences within a hard drive as expressed within a desktop environment was a great boon, both as a labour saving device (allowing freedom for more creativity) but also because it offered previously unimaginable ways to experiment with and re-assemble images. Metadata now replaced strips of films hanging on film bins.