Bastion of classiness and revolutionary in its day, Stockholm Design Lab's founder deciphers the avant-garde history of the interlocking Cs On visiting the NO 5 Culture Chanel exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris, curated byJean-Louis Froment, I was reminded of my favourite logotype and perfume.When Gabrielle Bonheur ’Coco’ Chanel launched Nº5 in 1921 it was a revolution in the perfume world. She presented a clean and simple bottle for the modern woman. At that time perfume names were poetic and often set in a script typeface, but Chanel decided to use a clinical approach for her first perfume. On a white label set in a simple sans serif, one could read only Nº5, CHANEL, PARIS.

While this product remains a milestone in the history of modernity, its origins remain somewhat mysterious and arcane. As Chanel was deeply embedded in the Parisian art world, surrounded by influential artists such as Jean Cocteau, Guillaume Apollinaire and Picasso, it’s not too unlikely that she was also aware of and inspired by the city’s Dada movement, led by Tristan Tzara and Francis Picabia. Indeed the Dada butterflies (‘papilllons Dada’ — very short texts printed on white or coloured paper), had the same radical aesthetic.

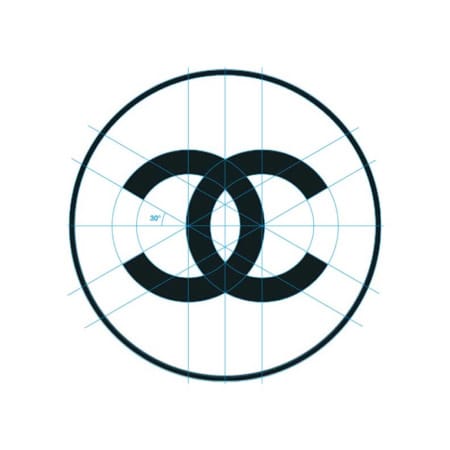

This stark simplicity extended to every aspect of the design. By placing an uppercase ‘C’ on the black wax seal of the neck of her perfume bottle and doubling it, Coco Chanel turned the letterform into a striking monogram. The inspiration for this is believed to come from several sources. For instance, these interlaced curves were also to be found in the stained glass windows of the church of Aubazine, where that the orphaned Coco spent much of her formative youth.

Catherine de´Medici may also have had a hand in Mademoiselle Chanel’s design decisions. Born in 1519 and raised in a convent just like Coco, she became queen of France in 1549 and widowed in 1559, henceforth choosing to wear only black — her monogram was formed from a double C.

Yet another legend is found in Tilar J. Mazzeo’s book The Secret of Chanel Nº5 — “One summer night Coco Chanel looked up at a vaulted arch at one of Irène Bretz’s famous parties at Château Crémat and found inspiration in a Renaissance medallion: two interlocking Cs.”

Though its references appear to span several centuries of French history, the untouched CC monogram and the Chanel logotype (the angle and weight of the monogram C is 30° while the wordmark C is 27°), still resonates as a modern archetype almost 100 years after its inception.

stockholmdesignlab.se

Nº5

Chanel Nº5 was developed by French master perfumer Ernest Beaux. He based the scent on an earlier work, Le Bouquet de Catherine, released in 1913 to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the Romanoff dynasty (Beaux worked for A. Rallet and Company, the official perfumer to the Russian royal family). War prevented the commercial success of this product, but played a crucial role in what was to become Chanel’s first fragrance. Beaux took the rose and jasmine architecture of Catherine and, inspired by his time fighting for the White Russian Army in the Arctic, adapted it to capture the stark purity of that landscape by manipulating aldehydes to create a unique “winter” note.

Counterfeit Coco

All luxury brands have to combat trade in faked versions of their wares. Chanel Nº5 is a victim of its own success in this regard, standing as one of the most frequently counterfeited fragrances. The relative simplicity of the bottle, box and graphic design means that this highly desirable product requires a relatively low level of skill for its imitation. This duplicity has become such a part of Nº5‘s history that the Annette Green Fragrance Archive at the Los Angeles FIDM Museum holds an example of the faked packaging as a historically valuable item.

March 20, 2014 3 minutes read

Fifth Element

Bastion of classiness and revolutionary in its day, Stockholm Design Lab's founder decipher the avant-garde history of those interlocking Cs